Battle of Iron Works Hill

| Battle of Iron Works Hill | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Revolutionary War | |||||||

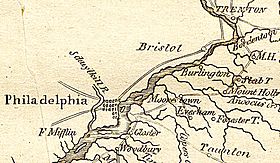

Map, c. 1806, showing towns most relevant to the Battle: Bordentown, Moorestown and Mount Holly, NJ. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 500–600 militia[1][2] | 2,000 British and Hessian troops[3] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Minor (see Aftermath)[4] | Minor (see Aftermath)[4] | ||||||

Location within New Jersey | |||||||

The Battle of Iron Works Hill, also known as the Battle of Mount Holly, was a series of minor skirmishes that took place on December 22 and 23, 1776, during the American Revolutionary War. The fighting took place in Mount Holly, New Jersey, between an American force mostly composed of colonial militia under Colonel Samuel Griffin and a force of 2,000 Hessians and British regulars under Carl von Donop.

While the American force of 600 was eventually forced from their positions by the larger Hessian force, the action prevented von Donop from being in his assigned base at Bordentown, New Jersey, and in a position to assist Johann Rall's brigade in Trenton, New Jersey, when it was attacked and defeated by George Washington after his troops crossed the Delaware on the night of December 25–26, 1776.[5][6]

Background

[edit]

In July 1776 forces of Great Britain under the command of General William Howe landed on Staten Island. Over the next several months, Howe's forces, which were British Army regulars and auxiliary German troops usually referred to as Hessian, chased George Washington's Continental Army out of New York City and across New Jersey.[7] Washington's army, which was shrinking in size due to expiring enlistments, and desertions due to poor morale, took refuge in Pennsylvania on the western shore of the Delaware River in November, removing all the available watercraft to deny the British any opportunity to cross the wide river.[8]

General Howe established a chain of outposts across New Jersey, and ordered his troops into winter quarters. The southernmost outposts were located at Trenton and Bordentown.[9] The Trenton outpost was manned by about 1,500 men of a Hessian brigade under the command of Johann Rall, and the Bordentown outpost was manned by Hessians and the British 42nd Regiment contingents, about 2,000 troops in all, under the command of the Hessian Colonel Carl von Donop.[3] Bordentown itself was not large enough to house all of von Donop's force. While he had hoped to quarter some troops even further south at Burlington, where there was strong Loyalist support, floating gun batteries from the Pennsylvania Navy threatened the town, and Donop, rather than expose Loyalist allies to their fire, was forced to scatter his troops throughout the surrounding countryside.[10]

As the troops of von Donop and Rall occupied the last outposts, they were often exposed to the actions of rebel raids and the actions of Patriot militia forces that either arose spontaneously or were recruited by Army regulars. These actions frayed the nerves of the troops, as the uncertainty of when and where such attacks would take place, and by what size force, put the men and their commanders on edge, leading them to jump up to investigate every rumored movement. Rall went so far as to order his men to sleep "fully dressed like [they were] on watch."[11]

One militia force that rose in December 1776 was a company under the command of Virginia Colonel Samuel Griffin. Griffin (whose name is sometimes misspelled "Griffith") was the adjutant to General Israel Putnam, who was responsible for the defense of Philadelphia. Griffin's force, whose exact composition is uncertain, probably included some Virginia artillerymen, Pennsylvania infantry, and New Jersey militia, and numbered five to six hundred.[1][2] By mid-December he had reached Moorestown, about ten miles southwest of Mount Holly.[12][13] By December 21, Griffin had advanced to Mount Holly and established a rough fortification atop a hill near an iron works, south of the Rancocas Creek and the village center.[14] Von Donop sent a Loyalist to investigate, who reported a force of "not above eight hundred, nearly one half boys, and all of them Militia a very few from Pennsylvania excepted".[1] Thomas Stirling, who commanded a contingent of the 42nd positioned about seven miles north of Mount Holly at Blackhorse (present-day Columbus), heard rumors that there were 1,000 rebels at Mount Holly and "2,000 more were in the rear to support them".[1] When von Donop asked Stirling for advice, he replied, "You sir, with the troops at Bordentown, should come here and attack. I am confident we are a match for them."[15]

Battle

[edit]

On December 21, about 600 of Griffin's troops overwhelmed a guard outpost of the 42nd located about one mile south of Blackhorse at Petticoat Bridge.[16][17] On the evening of December 22, Washington's adjutant, Joseph Reed, went to Mount Holly and met with Griffin. Griffin had written to Reed, requesting small field pieces to assist in their actions, and Reed, who had been discussing a planned attack on Rall's men in Trenton with Washington, wanted to see if Griffin's company could participate in some sort of diversionary attack. Griffin was ill, and his men poorly equipped for significant action, but they apparently agreed to some sort of actions the next day.[18]

On the morning of December 23, von Donop brought about 3,000 troops (the 42nd British (Highland) Regiment and the Hessian Grenadier battalions Block and Linsing) to Petticoat Bridge where they overwhelmed Griffin's men. Griffin's troops retreated to Mount Holly where von Donop reported scattering about 1,000 men near the town's meeting house. Jäger Captain Johann Ewald reported that "some 100 men" were posted on a hill "near the church", who "retired quickly" after a few rounds of artillery were fired.[19] Griffin, whose troops had occupied Mount Holly, slowly retreated to their fortified position on the hill, following which the two sides engaged in ineffectual long-range fire.[20]

Aftermath

[edit]

Von Donop's forces bivouacked in Mount Holly on the night of December 23, where, according to Ewald, they plundered the town, breaking into alcohol stores of abandoned houses and getting drunk.[15] Von Donop himself took quarters in the house that Ewald described as belonging to an "exceedingly beautiful widow of a doctor",[15] whose identity is uncertain.[21][22] Recent research, including genealogical tracking, points to Mary Magdeline Valleau Bancroft. Mary fits the criteria.[23] According to records of captures by the militia, Samuel Griffin captured a Dr. Daniel Bancroft a few days before the battle and led him away as being a Tory spy. Dr. Bancroft had married Mary Magdalene Valleau, a niece raised by Dr. Peter Bard and his wife, relatives of the owners of the iron works in town. Royal forces subsequently razed those works during their second visit to Mount Holly, in 1778, "because of rebel activity there".

Mary had just turned 18 at the time of her marriage in September 1776. A diarist describes her: "At the period of which we are now speaking she had just entered her eighteenth year, and was possessed of an elegant figure, a fascinating manner, and was endowed with great conversational powers, all of which caused her to be esteemed a beauty." Subsequent information indicates, in December 1776, she was staying with a family near Mount Holly and feared her husband had died. Her best option was to secure his release through diplomacy with Colonel Von Donop.

The next day, December 24, they moved in force to drive the militia from the hill, but Griffin and his men had retreated to Moorestown during the night.[20] For whatever reason, von Donop and his contingents remained in Mount Holly, 18 miles (29 km) and a full day's march from Trenton,[24] until a messenger arrived on December 26, bringing the news of Rall's defeat by Washington that morning.[20][25]

News of the skirmishes at Mount Holly was often exaggerated. Published accounts of the day varied, including among participants in the battle. One Pennsylvanian claimed that sixteen of the enemy were killed, while a New Jersey militiaman reported seven enemy killed.[4] Both Donop and Ewald specifically denied any British or German casualties occurred during the first skirmish on December 22,[22] while the Pennsylvania Evening Post reported "several" enemy casualties with "two killed and seven or eight wounded" of the militia through the whole action.[4]

Some reporters, including Loyalist Joseph Galloway, assumed that Griffin had been specifically sent to draw von Donop away from Bordentown, but von Donop's decision to attack in force was apparently made prior to Reed's arrival. Reed noted in his journal that "this manouver [sic], though perfectly accidental, had a happy effect as it drew off Count Donop ...."[4] The planning for Washington's crossing of the Delaware did include sending a militia force to Griffin in an attack on von Donop at Mount Holly; this company failed to cross the river.[26]

Legacy

[edit]The hill that Griffin's militia occupied is located at Iron Works Park in Mount Holly. The battle is reenacted annually.[27]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Fischer 2004, p. 198.

- ^ a b Dwyer 1983, p. 211.

- ^ a b Dwyer 1983, p. 151.

- ^ a b c d e Dwyer 1983, p. 216.

- ^ Rosenfeld 2006, p. 177.

- ^ Di Ionno 2000, p. 29.

- ^ Dwyer 1983, p. 5.

- ^ Dwyer 1983, pp. 24–112.

- ^ Fischer 2004, p. 185.

- ^ Dwyer 1983, pp. 170–173.

- ^ Fischer 2004, p. 196.

- ^ Dwyer 1983, p. 213.

- ^ Hunt, December 19, 1776: "... the Soldiers had Taken our Meeing house [in Moorestown] to Lodge in ..."

- ^ Rizzo 2007, p. 80.

- ^ a b c Fischer 2004, p. 199.

- ^ Petticoat Bridge is located on the map, c. 1806, where the road leading north from Slab Town crosses the nearest creek, which is Assiscunk Creek.

- ^ Hunt, December 22, 1776: "we had a pretty good Quiet Meeting at our Meeting [in Moorestown] the Soldiers being gone"

- ^ Reed 1847, p. 273.

- ^ Dwyer 1983, pp. 214–215.

- ^ a b c Rizzo 2007, p. 82.

- ^ Fischer 2004, p. 200.

- ^ a b Dwyer 1983, p. 215.

- ^ "Garden_State_Legacy". www.gardenstatelegacy.com. Retrieved 2024-10-15.

- ^ Fischer 2004, p. 216.

- ^ Hunt, "Memorandom 24th of the 12 mo: 1776" "...but things Seemed to turn very Strange and unexpected about the 22 of the 12 mo. the two armies Met at Mount Holly and had a Scermish. the Americans were Drove out of the town and Came back to the Moorestown and by Reports the Hessians on the English party did Strip many very much at that time in Mt Holly. maybe 20 years before this Mt Holly was a Remarkably hilly favourd place but there was an Admirable Strange turn for as was Reported about the 26 of the month a very Stormy Day Some Hundreds of the Hessians or of the English party were taken Prisoners at Trentown & Brought to Phil and the Rest Drove back towards Brunswick."

- ^ Dwyer 1983, p. 241.

- ^ "Battle of Iron Works Hill reenactment". Main Street Mount Holly. Archived from the original on March 7, 2008. Retrieved 2010-01-04.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link)

- Di Ionno, Mark (2000). A Guide to New Jersey's Revolutionary War Trail: For Families and History Buffs. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 0-8135-2770-8.

- Dwyer, William M. (1983). The Day is Ours!. New York: Viking. ISBN 0-670-11446-4.

- Fischer, David Hackett (2004). Washington's Crossing. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-518159-X.

- Hunt, John (1776). John Hunt Journal. Swarthmore, PA: SFHL-RG5-240, Friends Historical Library of Swarthmore College.

- Reed, William Bradford (1847). Life and Correspondence of Joseph Reed, Volume 1. Lindsay & Blakiston.

- Rizzo, Dennis (2007). Mount Holly, New Jersey: A Hometown Reinvented. The History Press. ISBN 978-1-59629-276-5.

- Rosenfeld, Lucy D. (2006). History Walks in New Jersey: Exploring the Heritage of the Garden State. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 0-8135-3969-2.

Further reading

[edit]- Federal Writers' Project of the Works Progress Administration for the State of New Jersey (2007). New Jersey: A Guide to Its Present and Past. Murrieta, CA: US History Publishers. ISBN 978-1-60354-029-2.

External links

[edit]